Volcanic activity

This page provides messages about volcanic activity.

In this section:

- Reduction: Reduce the impacts of volcanic activity

- Readiness: Get prepared to respond to volcanic activity

- Response: What to do during volcanic activity

- Recovery: What to do after volcanic activity

- Volcanic unrest is increased activity that may or may not lead to a volcanic eruption. Volcanic unrest can produce hazards on or near a volcano, such as volcanic earthquakes, gas emissions and land deformation.

- Volcanic eruptions produce several near and far-reaching hazards. Volcanic eruptions can last for days, weeks, months, or years. The most widespread and disruptive hazard is usually volcanic ash.

- Make and practise your emergency plan, make a grab bag and have emergency supplies.

- Find out from your local Civil Defence Emergency Management Group what the volcanic risk in your area is and know how to stay informed.

- Follow official advice provided by your local Civil Defence Emergency Management Group, the Department of Conservation (for visitors to the Tongariro and Taranaki National Parks), local authorities and emergency services both during and following volcanic activity.

- If a volcano is active, minimise your time near the volcano especially the summit region and valleys. During volcanic activity, near-volcano hazards may be present. If you are in an exposed area and become aware of near-volcano hazards, the best way to protect yourself is to quickly move (run or drive if you can) as far away as possible from the volcano.

- If ash fall has been forecast for your region, before ash fall starts, if possible, go home to avoid exposure to, and driving during, ash fall.

A volcano is an opening in Earth’s crust through which molten rock, volcanic ash and gases can reach the surface.

Volcanic unrest is increased activity that may or may not lead to a volcanic eruption. Volcanic unrest can produce hazards on or near a volcano, such as volcanic earthquakes, gas emissions and land deformation. Some volcanic unrest can only be detected by monitoring instrumentation. Most volcanic eruptions follow unrest, but not all unrest episodes lead to volcanic eruptions. This makes managing unrest challenging for scientists and Civil Defence Emergency Management, and means that you might find unrest unsettling. Unrest can last for days, weeks, months, or years.

Volcanic eruptions produce several near- and far-reaching hazards. Volcanic eruptions can last for days, weeks, months, or years. The most widespread and disruptive hazard is usually volcanic ash.

New Zealand is situated between the Australian and Pacific Plates on the “Ring of Fire” around the Pacific Ocean. The Ring of Fire contains most of the Earth’s active volcanoes.

New Zealand has 11 active volcanic areas (above the water):

- Eight are in the North Island:

- Auckland Volcanic Field

- Northland (Bay of Islands and Whangarei Volcanic Fields)

- Okataina Volcanic Centre (including Tarawera)

- Rotorua Volcanic Centre

- Ruapehu

- Taranaki

- Taupō Volcanic Centre

- Tongariro Volcanic Centre (including Ngauruhoe, Te Maari and Red Crater)

- Three are offshore:

- Kermadec Islands (Raoul and Macauley islands)

- Tuhua | Mayor Island

- Whakaari | White Island

There are also many more underwater volcanoes in the Kermadec Volcanic Arc between the North Island and Tonga.

More information on New Zealand’s volcanoes is available on the GNS Science website.

Volcanoes come in different shapes and sizes. There are three main types in New Zealand:

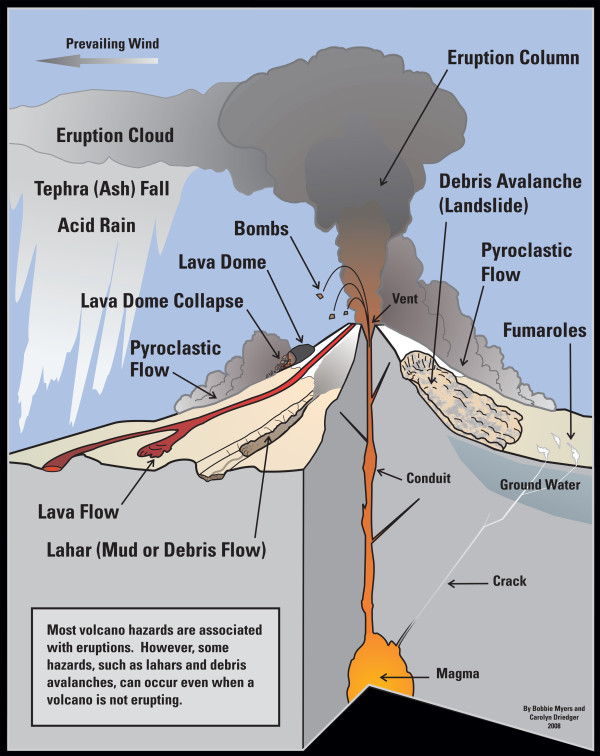

- Cone volcanoes (also called stratovolcanoes), such as Whakaari/White Island, Ruapehu, Taranaki and Tongariro/Ngauruhoe. Cone volcanoes are characterised by a series of frequent (every 10 to fifty years) small to moderate eruptions from roughly the same point on the Earth’s surface. Erupted rocks build up to form a volcanic cone. Cone volcanoes produce many hazards, including lava flows, ashfall, lahars, pyroclastic flows and landslides.

- Volcanic fields, such as the Auckland Volcanic Field, where eruptions have happened at (at least) 53 different places so far. Volcanic fields form when small eruptions (compared to cones and calderas) occur over a wide area. Despite the eruptions being relatively small, the impacts in New Zealand’s largest city can be catastrophic. These eruptions are spaced over long time intervals, with each eruption building a single small volcano that usually does not erupt again. Some eruptions form hills, such as Mount Eden, and some form explosion craters, such as Orakei Basin. Because each eruption occurs in a different place, the location of the next eruption cannot be predicted until it is imminent. We may only get hours to days’ notice of a new eruption of the Auckland Volcanic Field.

- Caldera volcanoes, are large volcanic centres such as across the central Taupō Volcanic Zone (the area from Taupō to Tarawera) and Tuhua/Mayor Island. The most frequent activity is unrest. Unrest is very likely in a lifetime. Moderate eruptions are unlikely, but possible, in your lifetime. Calderas form by the collapse of a volcano into itself, making a large volcanic basin, such as the one now filled by Lake Taupō. Large, caldera-forming eruptions are extremely rare (tens of thousands of years apart) and extremely unlikely in your lifetime. In the last 30,000 years, there have been 12 moderate to large eruptions in the Okataina area (including Tarawera) and 26 in the Taupō The most likely location for the next unrest or eruption activity is in these two areas.

More information on the types of volcanoes in New Zealand is available on the GNS Science website.

Volcanic eruptions in New Zealand have injured and killed people and destroyed property. For example, the eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1886 killed at least 106 people, and a lahar on Mount Ruapehu in 1953 caused the deaths of 151 people in the Tangiwai railway disaster. In 2019, 22 lives were lost and 25 people were injured following an explosive eruption on Whakaari/White Island.

New Zealand volcanoes produce a range of hazards and have different levels of volcanic unrest or eruptive activity. Whakaari/White Island and Tongariro (especially Ngauruhoe) have been the most frequently active volcanoes in our recorded history, closely followed by Ruapehu. Some of our other volcanoes can have hundreds or even thousands of years between eruptions.

Volcanic hazards can be divided into four groups: geothermal activity, volcanic unrest, near-volcano eruption hazards and far-reaching eruption hazards.

Geothermal activity is often associated with volcanic activity. Geothermal activity occurs when groundwater is heated by hot rock or magma. In some parts of New Zealand, geothermal activity forms long-lived features such as hot pools, boiling mud pools, geysers and fumaroles. Volcanic activity can increase geothermal activity. Geothermal activity can cause burns from the hot water and steam. See the Geothermal Activity section for more information on geothermal hazards.

Volcanic unrest hazards occur on and near the volcano, and can include:

- Earthquakes: Earthquakes are usually unrelated to volcanic activity, but they can also be caused by magma moving, and pressure building, inside or beneath a volcano. See the Earthquake section for more information on earthquake hazards.

- Gases: Volcanic unrest may be accompanied by increased volcanic gas emissions. Magma contains dissolved gases, which are released via the volcanic conduit into the atmosphere as magma approaches the Earth’s surface. Carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur gases such as hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and sulphur dioxide (SO2) are the hazardous gases which are most likely to be emitted during unrest. Some volcanic gases are heavier than air and can build up in confined spaces such as hollows, caves, and sometimes rooms in buildings, displacing oxygen. In high concentrations, these gases can be lethal to people and animals.

- Land deformation: Changes to the ground surface, such as swelling, sinking, or cracking are often associated with volcanic unrest or as a result of volcanic eruption. Land deformation can directly damage homes, cause landslides and change the risk of flooding as the ground moves. See the Landslide section for more information on landslide hazards. See the Flood section for more information on flood hazards.

- Landslides (debris avalanches): The sudden collapse of unstable rock, mud, sand, and soil, from the side of a volcano. Landslides can happen at any mountain where the slope of the mountain has become less stable, but they are commonly associated with volcanic activity because the volcanic mountain is weakened by magma moving and pressure building inside. At the largest scale, collapses of whole sections of a volcano can occur. See the Landslide section for more information on landslide hazards.

Near-volcano eruption hazards can be highly destructive and dangerous near an active volcano, impacting 3-5 km from the vent. Some near-volcano hazards can extend up to 10-20 km away from the eruption site. In rare cases, near-volcano hazards may reach beyond 20 km. They can include:

- Ash falls: Small (less than 2 mm) jagged pieces of rock and glass produced by explosive eruptions and transported downwind. Close to volcanoes, ash can be thick enough to collapse roofs and cause structural damage to buildings. Even thin layers can cause serious disruption to lifeline utilities, such as water and electricity networks. Small amounts of ash can make driving dangerous.

- Ballistics: Lava and rock fragments, from centimetres to tens of metres in size, which are ejected from the volcano vents along fast, cannonball-like trajectories. Ballistics are lethal and highly damaging. They can travel hundreds of metres to a few kilometres from the eruption site. Along with pyroclastic flows, ballistic hazards are the main reason for evacuations near an active volcano.

- Earthquakes: Earthquakes are usually unrelated to volcanic activity, but they can also be caused by eruptions, magma moving, and pressure building inside or beneath a volcano. See the Earthquake section for more information on earthquake hazards.

- Floods: Rainfall events, days to weeks after a volcanic eruption can lead to remobilisation of volcanic ash. When fine ash covers soil and reduces infiltration, it can cause increased runoff and flooding when it rains. Some of these vents can behave as lahars. See the Flood section for more information on flood hazards.

- Gases and aerosols: Emissions of gases including carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrogen chloride (HCl), and sulphur gases (H2S and SO2) increase during eruptions:

- Near vents and volcanoes, volcanic gases are irritating to eyes, skin, and breathing, and can be lethal at high concentrations.

- Some volcanic gases are heavier than air and can build up in confined spaces such as hollows, caves, and sometimes rooms in buildings, displacing oxygen. In high concentrations, gases can be lethal to people and animals.

- Acid rain can occur when rain falls through a plume of gases and aerosols, particularly if there are high concentrations of volcanic gases. Close to the vent, rainfall can be as acidic as freshly squeezed lemon juice. Acid rain can irritate the skin and eyes or cause a stinging sensation. If acid rain occurs for a sustained period, it can also damage plants, and accelerate the rusting of metal surfaces on buildings, vehicles, farm equipment, and infrastructure components, including plumbing fittings which can result in the contamination of drinking water. It may also affect the quality of surface waters, and may kill fish in open ponds.

- “Vog” (volcanic smog) is caused by volcanic gases reacting in the atmosphere. Vog is visible as a haze and is blown downwind. Vog can be irritating to breathing and may cause persistent health problems. More information on vog is available on the International Volcanic Health Hazards Network website.

- Lahars (volcanic mudflows): A hot or cold, dense mixture of water, rock, mud, sand, and soil, that flows rapidly downstream. Lahars form in a variety of ways, usually by the rapid melting of snow and ice by hot volcanic debris, intense rainfall on loose volcanic deposits, breakout from a lake dammed by volcanic deposits or an eruption through a crater lake. Lahars can occur long after an eruption has ceased, usually when there is heavy rain. Lahars are lethal and highly destructive to anything in their path.

- Land deformation: Changes to the ground surface, such as swelling, sinking, or cracking. Land deformation can directly damage homes, cause landslides and change the risk of flooding as the ground moves. See the Landslide section for more information on landslide hazards. See the Flood section for more information on flood hazards.

- Landslides (debris avalanches): The sudden collapse of unstable rock, mud, sand, and soil, from the side of a volcano. Landslides can happen at any mountain where the slope of the mountain has become less stable, but they are commonly associated with volcanic activity because the volcanic mountain is weakened by magma moving and pressure building inside. At the largest scale, collapses of whole sections of a volcano can occur. See the Landslide section for more information on landslide hazards.

- Lava flows: Streams of molten rock that pour from an eruption site and flow down valleys. You can generally avoid lava flows, as they usually cover new ground slowly, but they will destroy everything in their path. Lava flows set fire to buildings, infrastructure, and vegetation, can cause dangerous explosions, and toxic smoke from lava flows can travel hundreds of metres.

- Pyroclastic flows: Extremely fast-flowing mixtures of hot gases and volcanic rock that form when eruption columns or lava domes collapse. They flow down, and sometimes beyond, the slopes of the volcano, and are lethal and highly destructive. Along with ballistics, pyroclastic flows are the main reason for evacuations.

- Pyroclastic surge: a fluid mass of turbulent gas, water, steam and rock fragments that is ejected during a volcanic eruption. They are similar to pyroclastic flows, but they have a lower density because they include more gas, steam and/or water. This allows them to rise over ridges and hills. These are common if the eruption occurs through hydrothermal systems, wet ground or a crater lake.

- Tsunami: A volcanic eruption or landslide into water can generate extremely destructive tsunami waves. See the Tsunami section for more information on tsunami hazards.

- Wildfire: Volcanic eruptions (especially lava flows) can set fire to buildings, infrastructure, and vegetation, which can spread quickly, particularly in dry conditions and in urban areas.

Far-reaching eruption hazards, beyond 10-20 km from the eruption site, are usually disruptive rather than destructive. They can include:

- Ash falls: Small (less than 2 mm) jagged pieces of rock and glass produced by explosive eruptions and transported downwind. Ash fall is the most likely volcanic hazard for most people in New Zealand. Eruptions from volcanoes such as Taranaki, Ruapehu, and Tongariro (including Ngauruhoe), will likely produce light to heavy ash falls in downwind areas. Ash can be thick enough to collapse roofs at a distance from volcanoes especially if ash is not removed and becomes wet and heavy on weaker structures. Breathing airborne volcanic ash can cause short-term symptoms such as a cough and sore throat, and may have more serious health effects for some people and animals. Volcanic ash can also disrupt air traffic and road transport and cause power and water outages.

- Earthquakes: Earthquakes are usually unrelated to volcanic activity, but they can also be caused by magma moving, and pressure building inside or beneath a volcano. See the Earthquake section for more information on earthquake hazards.

- Floods: When fine ash covers soil and reduces infiltration, it can cause increased runoff and flooding when it rains. See the Flood section for more information on flood hazards.

- Gases and aerosols: During eruptions, plumes of volcanic gases and sulphate aerosol are blown downwind. Gases and aerosols can be harmful to health, vegetation and infrastructure. The most common volcanic air pollutant that may cause problems in downwind communities during a volcanic eruption is vog (volcanic smog), caused by volcanic gases reacting in the atmosphere to form sulphate aerosol. Vog is visible as a haze and is blown downwind. Vog can be irritating to breathing and may cause persistent health problems. More information on vog is available on the International Volcanic Health Hazards Network website. More information on volcanic and geothermal gases is available on the International Volcanic Health Hazards Network website.

- Lahars (volcanic mudflows): A hot or cold mixture of water and volcanic debris that flows rapidly downstream. Lahars form in a variety of ways, usually by the rapid melting of snow and ice by hot volcanic debris, intense rainfall on loose volcanic deposits, breakout from a lake dammed by volcanic deposits or an eruption through a crater lake. Lahars can occur long after an eruption has stopped, usually when there is heavy rain. Lahars are lethal and highly destructive to anything in their path and can travel tens of kilometres or more from volcanoes.

- Tsunami: A volcanic eruption or landslide into water can generate extremely destructive tsunami waves. See the Tsunami section for more information on tsunami hazards.

- Wildfires: Volcanic eruptions can set fire to buildings, infrastructure, and vegetation, which can spread quickly, particularly in dry conditions and in urban areas.

More information on volcanic hazards is available on the GNS Science website.

Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/64/

Further information on health impacts of volcanic activity can be found here:

Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora website – keeping safe from volcanic ash